- Australia ▾

- Topographic

▾

- Australia AUSTopo 250k (2024)

- Australia 50k Geoscience maps

- Australia 100k Geoscience maps

- Australia 250k Geoscience maps

- Australia 1.1m Geoscience maps

- New Zealand 50k maps

- New Zealand 250k maps

- New South Wales 25k maps

- New South Wales 50k maps

- New South Wales 100k maps

- Queensland 10k maps

- Queensland 25k maps

- Queensland 50k maps

- Queensland 100k maps

- Compasses

- Software

- GPS Systems

- Orienteering

- International ▾

- Wall Maps

▾

- World

- Australia & New Zealand

- Countries, Continents & Regions

- Historical

- Vintage National Geographic

- Australian Capital Territory

- New South Wales

- Northern Territory

- Queensland

- South Australia

- Tasmania

- Victoria

- Western Australia

- Celestial

- Children's

- Mining & Resources

- Wine Maps

- Healthcare

- Postcode Maps

- Electoral Maps

- Nautical ▾

- Flags

▾

- Australian Flag Sets & Banners

- Flag Bunting

- Handwavers

- Australian National Flags

- Aboriginal Flags

- Torres Strait Islander Flags

- International Flags

- Flagpoles & Accessories

- Australian Capital Territory Flags

- New South Wales Flags

- Northern Territory Flags

- Queensland Flags

- South Australia Flags

- Tasmania Flags

- Victoria Flags

- Western Australia Flags

- Gifts ▾

- Globes ▾

Dear valued customer. Please note that our checkout is not supported by old browsers. Please use a recent browser to access all checkout capabilities

The Colours of a Continent: A History of the Aboriginal Flag

In a world heavy with emblems and insignias, where banners are born of wars, governments, and sporting associations, there are few flags that carry the poetic and political weight of Australia’s Aboriginal Flag. It is, in form, astonishingly simple—three colours, one circle, no stars, no coats of arms. And yet it speaks volumes. About history. About identity. About presence.

More than just a piece of cloth or a decorative motif to unfurl at parades, the Aboriginal flag is, in truth, a canvas of cultural continuity—declaring in three elemental colours a story that spans millennia.

To understand the flag is to understand its journey. This is not the story of an official emblem, born in the halls of government. It is the story of a statement. A line in the sand. A silent, powerful "We are here."

A Flag Is Born (1971)

To speak of the Aboriginal flag’s beginnings is to speak of its maker: Harold Thomas, a Luritja man of Central Australian descent. Born in Alice Springs in 1947 and later removed to South Australia under the government’s assimilation policies, Thomas would become an artist, an activist, and—whether he intended to or not—the creator of one of the most recognisable symbols of modern Australian history.

The year was 1971. The Aboriginal rights movement was swelling across the country, sparked by decades—centuries, in truth—of dispossession, discrimination, and silence. Marches were beginning to fill city streets. Legal battles were mounting. And while the movement had voices, leaders, placards, and purpose, it lacked something vital: a symbol. A banner to carry the weight of its cause.

It was in this atmosphere of protest and cultural revival that Harold Thomas designed the flag. Not for profit. Not for art’s sake. But for visibility.

Its three parts are as follows:

-

Black: occupying the top half of the flag, represents the Aboriginal people of Australia.

-

Red: the lower half, symbolising the red earth—the land itself—and the spiritual relationship to it.

-

Yellow Circle: in the centre, the sun, the giver of life, representing both physical and spiritual illumination.

No words. No frills. Just pure symbolism, striking in its contrast and balanced in its geometry.

In one unassuming design, Thomas had created a national identity that did not lean on the British crown, nor on colonial iconography. It was something different—something sovereign.

The First Hoisting: Adelaide and the Tent Embassy

The flag’s first appearance was at a land rights rally in Victoria Square, Adelaide, in 1971—fittingly, the heart of a city built upon land once rich with the dreaming of the Kaurna people.

But its true arrival came one year later, in 1972, when the flag was hoisted over a handful of tents planted defiantly on the lawn outside Parliament House in Canberra.

This was the birth of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, an act of peaceful resistance sparked by the McMahon government’s refusal to recognise Aboriginal land rights. What began as a single beach umbrella soon became a movement. And at the centre of it all, flying against the starkness of white architecture and colonial symmetry, was the Aboriginal flag.

To see it in that context was to understand its purpose. It was a statement of presence—a bold counterpoint to a national narrative that had long preferred Aboriginal people in the footnotes, not the headlines.

A Banner of Protest, Pride and Pain

Over the following decades, the Aboriginal flag became more than a political accessory. It became a fixture of almost every major Aboriginal event and movement in the country.

It appeared at land rights marches, at Invasion Day protests, at art festivals, community centres, funerals, and celebrations. It was daubed on jackets, painted on faces, flown from car aerials and back verandahs. It stood beside the casket of Eddie Mabo. It was raised alongside the Torres Strait Islander flag during NAIDOC Week, and paraded on the fields of the Dreamtime at the ‘G.

And everywhere it went, it quietly whispered the same message: We were here first. We are still here. We are not going anywhere.

1995: Official Recognition at Last

Despite its widespread use and emotional power, the flag wasn’t officially recognised by the Australian government until 14 July 1995.

In a move that was both necessary and long overdue, the Keating government formally proclaimed the Aboriginal flag—alongside the Torres Strait Islander flag—as a flag of Australia, protected under the Flags Act 1953. It was a watershed moment, giving the flag legal protection and official status.

To be clear, it was already de facto national. But now, it was de jure.

Still, the flag remained, in spirit and in origin, the property of Harold Thomas.

And therein lay the seed of future complications.

Ownership and the Copyright Quandary

Here lies one of the most curious chapters in the history of any national symbol.

While the flag belonged, symbolically, to a people, it belonged, legally, to its designer.

In 1997, the Federal Court of Australia ruled that Harold Thomas held the intellectual property rights to the flag as its author and creator. This meant that any commercial use of the flag—on merchandise, in media, even on sportswear—required his permission.

At first, this was a manageable arrangement. But as use of the flag expanded, Thomas licensed exclusive reproduction rights to certain companies, including WAM Clothing, who—somewhat ironically—began issuing cease-and-desist notices to Aboriginal organisations and sports bodies using the flag without paying licensing fees.

It was, in the eyes of many, an outrageous contradiction. That Aboriginal communities could be legally barred from using their own flag. That it could become a tool of exclusion rather than expression.

Debates flared in Parliament, on talkback radio, and across social media. Petitions sprang up. Aboriginal legal and cultural leaders demanded that the flag be freed.

To Thomas’s credit, he did not shy away. In interviews, he acknowledged the need to protect the flag from exploitation, but also the growing complexity of controlling it.

What began as a symbol of empowerment now risked becoming a case study in unintended consequences.

2022: The Flag Is Freed

After years of public outcry, and a sustained campaign led by Aboriginal organisations and their allies, a breakthrough came in January 2022.

The Australian Government purchased the copyright to the Aboriginal flag from Harold Thomas for $20 million—a payment designed not as a fee for a symbol, but as recognition for a lifetime of cultural and artistic contribution.

The agreement, crafted with care, ensured that the flag would now be freely usable by all Australians, without restriction, across all mediums and settings. From clothing to sports events, artworks to community gatherings—the flag was liberated.

Thomas retained moral rights as its creator, ensuring that the design could not be altered or misused. But the copyright itself—after half a century—now rested with the public.

In his official statement, Thomas said:

“I’m pleased that this arrangement protects the integrity of the flag and ensures it can be used by all Australians. The flag represents the timelessness of our people’s land and culture.”

With those words, the banner returned to its original purpose: a shared emblem of continuity and cultural pride.

Symbolism Without End

Let’s return to the design. Because its power lies, still, in its simplicity.

There are no animals, no crowns, no coats of arms. No white stars. No references to the British Empire. No Latin phrases about prosperity. Just three shapes, three colours, three elements of deep meaning.

-

The black remains not just a reference to skin tone, but a statement of Aboriginal identity—a visual presence in a country that too often pretended Aboriginal people were invisible.

-

The red earth is not merely terrain—it’s ancestry, bloodlines, spiritual connection, songlines. It is the substance of stories written not in ink but in ochre and memory.

-

The yellow sun is more than the source of light—it’s the metaphysical centre, a source of life and guidance across both time and country.

And unlike most national flags, the Aboriginal flag is not rooted in conquest. It is not a boast. It is not a claim. It is, rather, a truth.

The Flag and the Nation Today

In the Australia of today, the Aboriginal flag is no longer fringe or footnote. It flies on Sydney Harbour Bridge. It sits behind the Speaker’s chair in the House of Representatives. It’s carried by Olympians. Draped over stadiums. Projected onto opera houses. And, critically, raised alongside the national flag at civic and commemorative events.

It flies on Mabo Day, National Sorry Day, and NAIDOC Week. It is seen at both Invasion Day protests and citizenship ceremonies. It does not belong to one political side or another. It simply is—an ever-present reminder of the deeper story that underpins the one most often told.

And as movements for Voice, Treaty and Truth continue to unfold, the flag is ever there—watching, waiting, bearing witness.

In Closing: The Weight and Lightness of a Flag

Flags can be heavy things. They can be wielded like weapons or waved like badges. But the Aboriginal flag—when flown with intention—is neither. It is not an instrument of nationalism. It is not a substitute for reconciliation. But it is, indelibly, a reminder.

Of presence. Of survival. Of an ancient world still here, layered under the one so often mistaken for new.

It began with an artist and a vision. It was born of protest, became an icon, weathered legal wrangling, and emerged—fifty years later—as one of the most enduring symbols of modern Australia.

To see it today—flying in the breeze, stark against blue sky—is to see a kind of truth.

It is a banner that does not ask to be celebrated.

It asks to be understood.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Travel Writings / Product Reviews

Club Med Phuket: Our Full Week in Review

Whether you’re a family chasing a balance between togetherness and independence, a couple craving peace and cocktails, or simply someone ready to trade routine for ritual—this is your place.

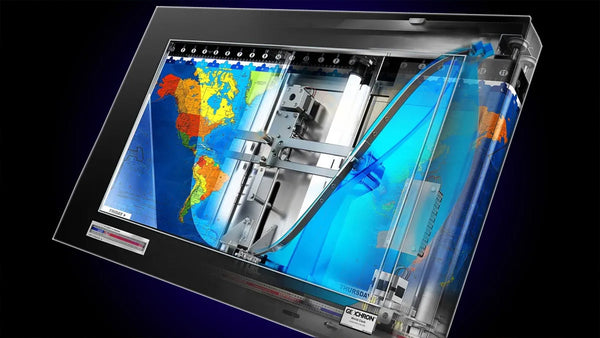

Where the Sun Never Sets: A Glorious History of Geochron World Clocks

The Geochron, whether mechanical or digital, offers more than information. It offers perspective. It reasserts the idea that we are part of a rotating story—lit by the sun, divided by clocks, and unified by the gentle ticking of planetary rhythm.

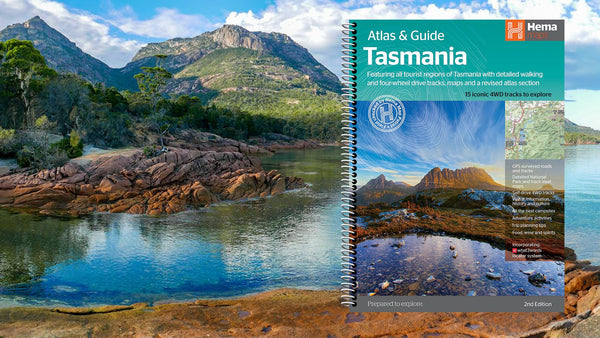

Tracks, Trails & Tassie Tales: A Rambler’s and Rover’s Guide to Tasmania

Tasmania doesn’t just offer adventure. It insists on it. It pulls you into its wilderness, tests your knees and diff locks, and then offers you a view that resets your understanding of beauty.

Christopher O'Keeffe

Author