- Australia ▾

- Topographic

▾

- Australia AUSTopo 250k (2025)

- Australia 50k Geoscience maps

- Australia 100k Geoscience maps

- Australia 250k Geoscience maps

- Australia 1:1m Geoscience maps

- New Zealand 50k maps

- New Zealand 250k maps

- New South Wales 25k maps

- New South Wales 50k maps

- New South Wales 100k maps

- Queensland 10k maps

- Queensland 25k maps

- Queensland 50k maps

- Queensland 100k maps

- Compasses

- Software

- GPS Systems

- Orienteering

- International ▾

- Wall Maps

▾

- World

- Australia & New Zealand

- Countries, Continents & Regions

- Historical

- Vintage National Geographic

- Australian Capital Territory

- New South Wales

- Northern Territory

- Queensland

- South Australia

- Tasmania

- Victoria

- Western Australia

- Celestial

- Children's

- Mining & Resources

- Wine Maps

- Healthcare

- Postcode Maps

- Electoral Maps

- Nautical ▾

- Flags

▾

- Australian Flag Sets & Banners

- Flag Bunting

- Handwavers

- Australian National Flags

- Aboriginal Flags

- Torres Strait Islander Flags

- International Flags

- Flagpoles & Accessories

- Australian Capital Territory Flags

- New South Wales Flags

- Northern Territory Flags

- Queensland Flags

- South Australia Flags

- Tasmania Flags

- Victoria Flags

- Western Australia Flags

- Gifts ▾

- Globes ▾

Dear valued customer. Please note that our checkout is not supported by old browsers. Please use a recent browser to access all checkout capabilities

Greenland for Sale? A Gall–Peters Perspective on Cartographic Ego and Arctic Aspirations

1. Introduction: A Map and a Misunderstanding

In 2019, the world paused briefly between climate collapse and constitutional crises to watch an unlikely international subplot unfold: the President of the United States expressed interest in buying Greenland.

Yes. Greenland.

A vast, icy landmass with a population smaller than Toowoomba and a GDP that wouldn’t power a mid-size shopping mall. An autonomous territory of Denmark, more snow than soil, with polar bears outnumbering post offices.

Why?

Well, depending on who you ask, it was about resources. Or military strategy. Or a final flourish of imperial theatre. But deep down, one suspects the real reason was cartographic delusion. A misunderstanding born not in diplomacy, nor in economics, but on the wall of every primary school classroom for the last 80 years.

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you: the Mercator projection.

And its long-overdue antidote: the Gall–Peters projection.

2. The Mercator Projection: Europe’s Favourite Lie

Let’s begin with the villain of the piece—Gerardus Mercator. A Flemish cartographer of the 16th century, Mercator’s great innovation was a world map that made navigation simple. By projecting the globe onto a cylinder, he ensured that straight lines on the compass translated to straight lines on the map. Genius! Seafaring efficiency! Longitude’s best friend!

There was, however, a catch. The Mercator projection preserved angles and direction, but it came at the cost of size. Specifically: areas near the equator shrank, and areas near the poles ballooned like a clown at a child’s birthday party.

Thus, Europe, North America, and that icy hulk Greenland all looked massive. Meanwhile, Africa—the second largest continent on Earth—was reduced to something resembling a misplaced footnote.

In short, the Mercator projection made the world look like a European conquest brochure. And for centuries, no one complained—because, frankly, Europe printed the maps.

3. Enter Gall–Peters: The Revenge of Proportionality

And then, in 1855, along came Reverend James Gall, a Scottish clergyman who suggested that perhaps we might like a map that didn’t massively distort land area. His idea went mostly unnoticed—possibly because he was also writing on theology and astronomy and Victorian people were busy having empires.

Fast-forward to 1973, when Dr Arno Peters, a German filmmaker and academic, resurrected Gall’s concept and renamed it the Gall–Peters projection. He didn’t invent it, but he marketed it like a cartographic messiah. Equal area! Anti-imperialist! Africa, finally shown in its actual, glorious enormity!

Cue the great map scandal of the 1970s.

The cartographic community gasped. There were meetings. Angry letters. Accusations of distortion (which was ironic, given Mercator's wildly inflated Greenland). But teachers, aid organisations, and socially conscious bureaucrats embraced it. The Gall–Peters projection offered a revolutionary idea: show countries not in terms of power or prestige, but in proportion to their actual size.

4. The Truth According to Gall–Peters

Now, before we go further, let’s compare some cold, hard numbers:

| Region | Mercator Appearance | Actual Area | Gall–Peters Portrayal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greenland | Similar to Africa | 2.1 million km² | Shrinks dramatically |

| Africa | Comparable to Greenland | 30.3 million km² | Towering and dominant |

| Europe | Dominant and central | 10.2 million km² | Smaller, rebalanced |

| South America | Tiny and tilted | 17.8 million km² | Stretched, impressive |

So while the Mercator map suggests you could walk across Greenland in the same time it takes to cross Nigeria, the Gall–Peters reminds you that Greenland is a chilly pancake compared to Africa’s continental feast.

This is not about aesthetics. The Gall–Peters map isn’t pretty. It’s lanky. It stretches continents into unfamiliar shapes. Australia looks like someone tried to roll it into pasta dough. But it’s honest. Every country is shown in proportion to its land area. No more puffed-up Sweden. No more diminutive Congo.

It’s not just a map. It’s a reprimand.

5. Trump, Greenland, and the Seduction of Size

Which brings us back to President Donald J. Trump, and the curious case of Greenland’s real estate potential.

In August 2019, multiple media outlets confirmed what sounded like satire: the President had floated the idea of buying Greenland from Denmark. This wasn’t whispered speculation—it was front-page news, complete with official statements and Danish eye-rolls.

Now, we are not here to judge the strategic value of owning a 2-million-square-kilometre frozen block of tectonic tranquility. Nor are we here to unpack the fact that Greenland is not for sale, and, if it were, it would politely decline.

What’s fascinating is how Greenland looked to the President.

Because when asked about the matter, Trump reportedly responded with bemused sincerity:

“Strategically it’s interesting and we’d be interested.”

Interesting indeed—if your understanding of Greenland’s size was based on, say, a Mercator projection. One could hardly blame him. After all, on the Mercator map, Greenland looks roughly the size of Africa, bigger than South America, and twice the size of the continental United States.

So if you’re thumbing through your briefing binder and glancing at a wall-mounted Mercator, you might reasonably conclude:

“My God. It’s huge. Let’s buy it before Canada gets there first.”

Had someone slipped him a Gall–Peters map, the pitch might’ve gone a bit differently:

“Sir, it’s actually quite small. And it’s mostly ice. And Denmark owns it.”

“Hmm. Still… could we put a hotel there?”

6. Cartographic Power Games

Maps are not neutral. They shape our worldview—sometimes literally. And the projection we choose influences how we see everything from global development to international prestige.

-

Mercator: Preserves angles and direction. Terrific for sailing. Terrible for truth.

-

Gall–Peters: Preserves area. Ugly, maybe. But morally satisfying.

-

Robinson: A compromise. Pleasing to the eye. Fudges everything equally.

And that’s the curious thing: nobody wants to hang a Gall–Peters projection on their wall. It’s the map you put up in a classroom if you want to make a point about colonialism and Eurocentrism. It’s the map your NGO insists on using. But it doesn’t feel right. It’s unfamiliar. It challenges what we thought we knew.

Which is exactly the point.

Because geography, like politics, is a story we tell ourselves. And most of us have been telling ourselves that Greenland is an Arctic juggernaut, when in fact, it’s more of a frosty footnote.

7. The Map as Metaphor

There is something oddly poetic about the Greenland episode. A man known for skyscrapers, pageants, and brand expansion sees a vast white shape on a map and thinks, “I could own that.” It’s classic cartographic hubris.

But it also reveals how deeply we’re shaped by the visual information we take for granted. A distorted map isn’t just a geographical error. It’s a cultural one.

The Mercator projection wasn’t malicious. It was a tool, built for a purpose. But that purpose has long passed. It remains on our walls not because it’s correct, but because it’s familiar.

The Gall–Peters, by contrast, is correct but confrontational. It says:

-

“Look again.”

-

“Question your assumptions.”

-

“No, Greenland is not the size of Africa.”

It is, in short, a map for grown-ups.

8. Greenland in the Gall–Peters World

Let’s take a moment to imagine the world according to the Gall–Peters projection, had it been the dominant map in schools, war rooms, and real estate brochures.

-

Africa would stand as the true titan it is—vast, central, rich in scale and scope.

-

South America would command the eye, a continent of gravity and grace.

-

Europe? Still culturally luminous, but no longer cartographically inflated.

-

And Greenland? A snowy whisper. A pristine periphery. Not a prize, but a place.

One imagines an alternate timeline where President Trump is handed a Gall–Peters map, studies it carefully, and says:

“Hmm. You know what? Maybe let’s leave Greenland alone. Let’s buy Puerto Rico again.”

9. What We Can Learn (Beyond the Ice)

This isn’t really about Greenland, or Trump, or Denmark’s icy patience. It’s about how we see the world, and how much of that vision is inherited from sources we never question.

The Gall–Peters map forces a re-evaluation. It reminds us that maps are not facts. They are interpretations. And that size matters—not in terms of importance, but in terms of justice.

Every time a child sees a Mercator map, they grow up believing Europe is huge, Africa is minor, and Greenland is formidable. The Gall–Peters says:

“Hold on. Let’s measure before we admire.”

It’s not a perfect map. But it’s a map that tells the truth about space, even if it bruises some egos along the way.

10. Conclusion: A Better Map, A Better World?

Will the Gall–Peters projection change the world? Probably not. People will still argue over borders. Real estate moguls will still eyeball archipelagos. And schools will still hang whichever map the head of geography prefers.

But perhaps, the next time someone proposes to buy a country, they’ll pause. They’ll consult a different map. One that doesn’t overstate the icy or understate the equatorial.

And when they look at Greenland—lean, vertical, modest in scale—they’ll say:

“You know what? Maybe we just admire it from afar.”

Because sometimes, understanding the world begins not with a journey, but with the right map.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Travel Writings / Product Reviews

The Colours of a Continent: A History of the Aboriginal Flag

It began with an artist and a vision. It was born of protest, became an icon, weathered legal wrangling, and emerged—fifty years later—as one of the most enduring symbols of modern Australia.

Club Med Phuket: Our Full Week in Review

Whether you’re a family chasing a balance between togetherness and independence, a couple craving peace and cocktails, or simply someone ready to trade routine for ritual—this is your place.

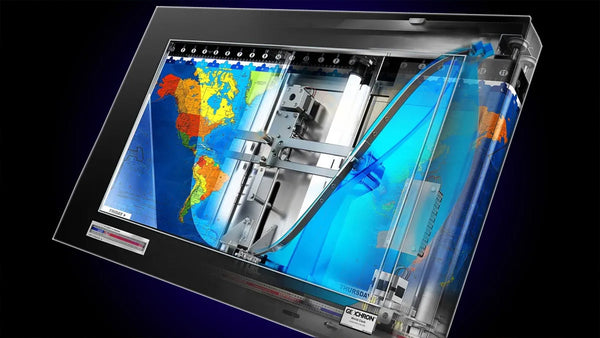

Where the Sun Never Sets: A Glorious History of Geochron World Clocks

The Geochron, whether mechanical or digital, offers more than information. It offers perspective. It reasserts the idea that we are part of a rotating story—lit by the sun, divided by clocks, and unified by the gentle ticking of planetary rhythm.

Christopher O'Keeffe

Author